Technology

How Blockchain Could Revolutionize Gold Trading

This publication recently sat down with a director from the UK's Royal Mint, which in partnership with US derivatives marketplace CME Group is launching a new digital currency to tokenize physical gold ownership.

Take an age-old asset class and merge it with a technology slated to be one of the most disruptive the world has seen. Sounds crazy, right?

That it may, in theory. But in practice, it makes perfect sense.

The Royal Mint, the UK government-owned bullion bar and coin producer, in partnership with CME Group, is using blockchain technology to transform gold trading as we know it today.

Using blockchain, which rose to fame in 2009 as the technology underpinning bitcoin, the Mint is “tokenizing” gold ownership by creating a digital gold currency whose value is linked to the price of the precious metal stored at its vault in Wales. Put simply, a blockchain is a virtual distributed ledger of transactions shared peer-to-peer that can record ownership across a public network of computers rendered tamper-proof by advanced cryptography.

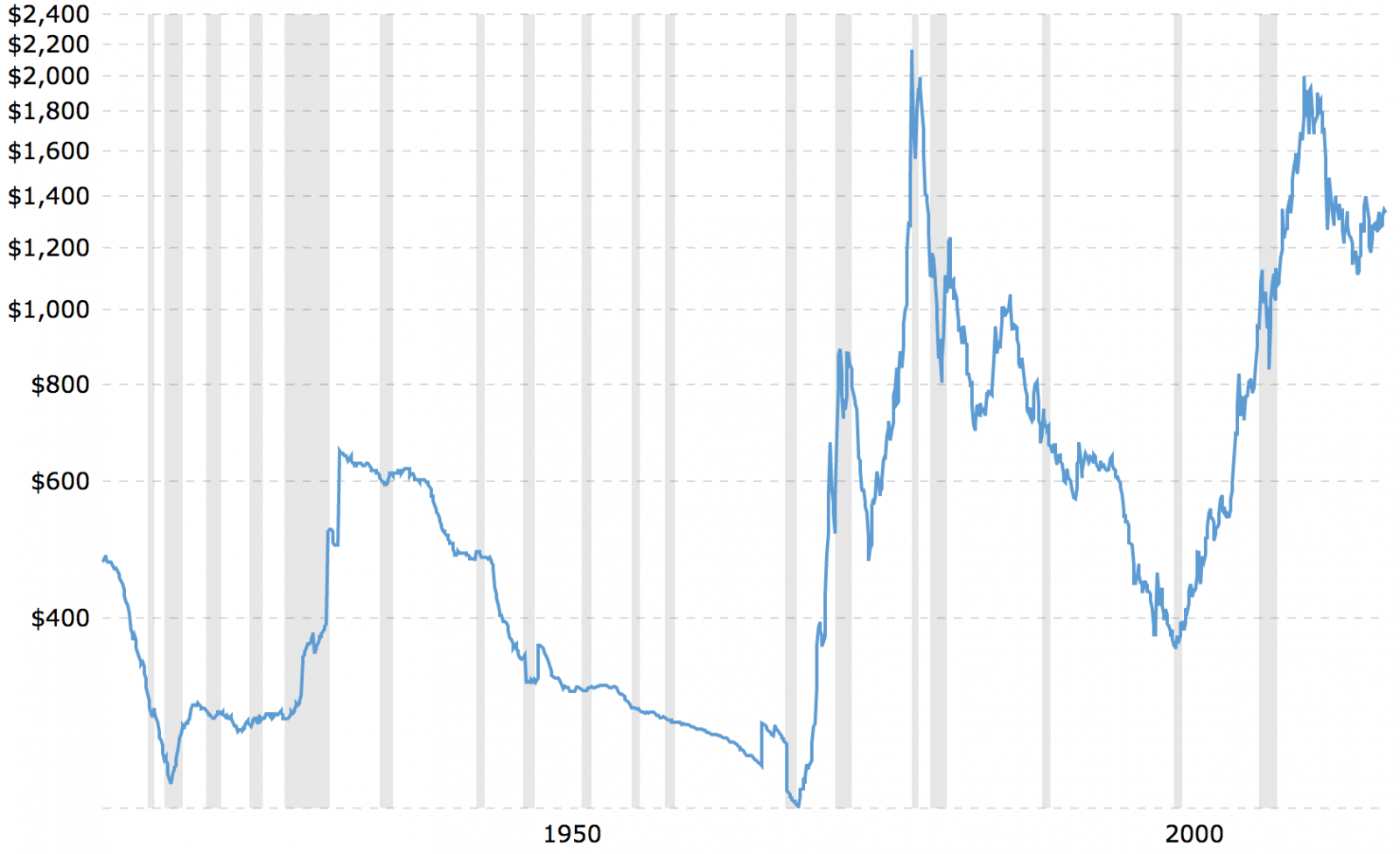

In the coming weeks, The Royal Mint will begin issuing digital tokens called Royal Mint Gold (RMG), with one token representing a single gram of real gold. Typically, gold is traded in ounces or larger measures, meaning the asset can be inaccessible to some investors given that the price of an ounce is around $1,300, plus storage and transfer fees.

Blockchain helps solve this problem, because tokenization makes gold immeasurably more divisible than it currently is. Each RMG is divisible up to six decimal places, meaning an investor could theoretically own one-millionth of a gram of gold – a near-impossible concept if extracting physical gold. Tokens are redeemable, too, so holdings in a digital wallet can be cashed in for physical gold.

“What we’re offering is a physical, tangible asset, ownership of which is demonstrated through ownership of the digital token(s) on the blockchain,” Tom Coghill, commercial director at RMG, told this publication on the sidelines of London Blockchain Week. “Physical gold investing can be challenging in terms of how you handle the expensive cost of storage, transfer etc. This means it becomes very inefficient when trading small amounts.

“Tokenisation opens investment potential from all corners of the market.”

RMG was conceptualized in 2013, four years before the meteoric rise of bitcoin and the crypto-currency market more generally. Coghill noted the advent of digital assets, and pointed out that a preference for digital payments is evidenced by a declining demand for coinage year-on-year.

“How does the Royal Mint ensure it stays relevant?” he asked. His answer: create a digital token with a stable value.

One of the biggest problems with bitcoin - depending on which side of the fence you sit - is its volatility. It is not unusual for bitcoin’s price to swing several thousand dollars in either direction daily, on the one hand rendering it useless as a store of value but ideal as a day trader’s play-thing.

But RMG is not, strictly speaking, a crypto-currency, Coghill explained, because its price directly reflects that of gold. This means it is highly unlikely that the token price will stray far from gold’s spot price because without physical backing, the digital coin would be worthless. The global gold market capitalization of nearly $8 trillion dwarfs the value of all crypto-currencies, currently valued at around $487 billion.

“I wouldn’t necessarily say what we have created is a crypto. What we have is physical gold placed on a blockchain, but in the digital asset market, there is clearly a need for a product with more price stability,” he said. Still, “the idea of making a digital coin was quite natural to us,” Coghill said, “us” referring to the 1,100-year-old Royal Mint.

Gold's price movements over the past 100 years. Source:

Macrotrends

Users’ identities must also be verified for exchange purposes. This means the model is inherently secure, Coghill explained.

“When we deliver, we need to know the identity of a wallet holder,” he said. “Even if tokens are hacked, the underlying asset could not be delivered.”

Scalability is crucial to the platform’s success, Coghill said. Currently, scale is measured in terms of how much bullion can be stored at the Royal Mint’s vault – “multiple billions of dollars’ worth,” he said. “Then, to scale the operation further, we are looking to build a network where ‘licensed’ operators extend the platform to their own client base.” An operator could be an asset manager or a broker, for example. The Royal Mint is in “advanced discussions” with potential operators that could distribute RMG to their clients, Coghill said, without providing names.

In today’s market, time is of the essence. Using RMG, gold trades are settled, on average, within two-and-a-half minutes, Coghill said. Charges are low, too, he said, and will be paid by the user as a premium to gold’s price. “It will always be a single basis-point or percentage charge,” he said, offering a gold exchange-traded fund (ETF) as a comparison, which might levy 50bps in fees annually.

Although the network of transactions is publicly-visible, the blockchain itself is privately-permissioned. In turn, The Royal Mint acts as the guardian of the RMG network, which allows for recovery measures to be put in place. Think of The Royal Mint as a hotel receptionist lending a hand after you locked yourself out of your room or misplaced your key.

Ultimately, The Royal Mint hopes the RMG network will resemble something like a peer-to-peer trading platform, on which users can quickly and efficiently execute trades in exchange for a very small fee. In the end, RMG is a mechanism for holding and moving value around the world; a digital gold currency. By providing this service, the Mint will earn its keep, plus the short-term profits from issuing gold.

“As the community continues to trade between themselves on our platform, the network charges for doing so,” Coghill said. “Over time, it becomes the ‘network effect’ of transfer value."