The following article explores the many facets of a multi-family office, going into definitions, the reasons why they are founded and the challenges in doing so, as well as how they should be effectively managed and aligned tightly with clients’ needs. These issues are evergreen because the MFO market remains as busy as ever in North America. Indeed, last year’s falls in global equities and the enactment of new tax laws in late 2017 only serve to remind ultra-high net worth families of the value of a good family office model.

In the third part of this feature, Jamie McLaughlin, chief executive of J H McLaughlin & Co, a member of FWR's editorial advisory board, and also a founder of the UHNW Institute, a not-for-profit organization, examines the themes. The article was adapted from James H McLaughlin, “Proscriptions and Prescriptions,” Investments & Wealth Monitor, January/February 2016.

The editors of this news service welcome feedback from readers who can email the editor at tom.burroughes@wealthbriefing.com

The UHNW Institute, in partnership with Family Wealth Report, is a non-profit educational initiative serving UHNW families and family offices. The team of industry experts will provide a curriculum in the form of articles, webinars and events throughout the year for their readers, which can be highlighted on our site. For more information, please visit www.uhnwinstitute.org.

The single biggest economic challenge facing MFOs and wealth-management firms generally is rightsizing pricing in the face of increasing complexity and demand for non-investment services, i.e. services where firms traditionally have lacked pricing power due to an unsystematic demand from client families.

Firms must demand to be paid for services rendered at a reasonable level of profitability. They must eschew families buying their services on price alone by simply walking away. The definition of an attractive and actionable client segment in any service industry is one where a firm can acquire and retain a client over a full business cycle, and at a predictable and attractive price point. Currently, there are woefully few firms with unique value, just good ones - so for good firms it’s all about doing just enough to acquire a client family and then ruthlessly managing costs. Sharper, more-disciplined pricing practices can get firms off this treadmill.

The first, immediate observation related to pricing is the remarkable variation of fee arrangements that exist. They are primarily bundled , but unbundling due to increasing client demand for non-investment services is occurring.

Where firms use asset-based fees there are some clear clustering patterns, but almost all firms that use asset-based fees use non-uniform discounts for clients above $50 million. These discounts may be offered to gather assets, but it’s economically perverse because these families are predictably more complex.

Where firms offer unbundled arrangements separating investment from non-investment services, there is little evidence that the non-investment service fees are derived from any reasonable or systematic cost-accounting model or controls. Many firms use a notional price for non-investment services best described as a professional service firm “time and effort” pricing model where the firm is taking a mark-up on its presumptive cost of time. In the absence of time tracking systems this is, at best, a notional pricing system where, in the absence of controls mitigating against “service creep,” there is ample evidence that many firms are delivering many of these discrete services at a loss.

Pricing for non-investment services

Supply and demand suggests that clients will pay a fair price for any service rendered, but this has been largely, untested for non-investment services such as planning and administration .

In fact, given firms’ traditional asset-based pricing models, clients have been socialized into thinking that they can get non-investment services for free embedded in a single bundled price. Firms have long used the pricing power of the investment mandate to cross-subsidize the non-investment services, but with demand shifting, families increasingly rank non-investment services as high-value prerequisites in their choice of provider. Further, they don’t want or expect to receive something for nothing, but firms have been too passive and have lacked the collective will to confront this issue.

While few firms can demonstrate sustainable economic value by their investment performance alone, many can demonstrate their value by delivering an array of non-investment services, most notably integrated planning-related advisory services such as tax and wealth transfer counsel whether directly or in conjunction with outside professional advisors. As

Wally Head, Vice Chairman of Gresham Partners, attests, “firms that provide documented economic value from non-investment services, lengthen and deepen their relationships with their clients.”

Insidious complexity

A final comment related to complexity deserves to be mentioned. MFOs must recognize complexity and anticipate it in their pricing, and not rely on families to understand their peculiarities or level of complexity because how are the families to know? Generally, they have no reference group. Some of the markers of complexity include the following:

-- Lots of professional advisors

-- Lots of decision-makers

-- Weak family-governance structures

-- Multiple generations and households

-- Varying levels of sophistication of family members

-- Transnational families/multiple jurisdictions/domiciles

-- Weak information-technology systems for information exchange and security; and

-- Widespread illiquidity including interests in closely-held operating businesses, real estate, and other limited-partnership investments.

Serving complexity confers pricing power

Complexity lies at the heart of why commercial service-providers either don’t serve the UHNW market segment or do so accepting lower margins and, as important, why families perceive they are not well-served by most commercial models, often choosing to do it themselves.

Wealth-management and professional service firms of many different stripes covet larger, inherently more-complex clients, but they are too often unable to deliver the needed services and, somewhat self-destructively, unable to be profitable serving these highly customized, idiosyncratic needs.

With the above as context, clients are increasingly aware that their complex service requirements have eclipsed many of their incumbent service providers such as investment firms, accounting firms, or other professional advisory firms.

Consequently, demand increasingly favors an approach anchored to a fully-integrated service platform that requires specialized staffing and is at the heart of serving the “whole client.” Such an integrated platform will place MFOs in a position to earn client primacy and, in time, improved business economics as primacy confers pricing power, which will act as a prophylactic against increasing asset-based fee compression.

Business economics collide with client experience

Separately, all wealth-management businesses, including MFOs, depend on top-line growth to some degree where performance and compensation management systems often favor asset gathering over client service delivery. Consequently, the discovery process is not fully disinterested and often comes with a sales bias where persuasion trumps analysis and the more nuanced feathering out of the true client need is often overlooked or neglected.

In summary, there is a great tension between firm business economics and the client experience.

In this environment, clients will increasingly seek to disintermediate manufacturers and distributors and should be more willing to pay the true costs for advice. Firms need to commit capital to staff at appropriate levels to provide this advice and or confederate with other advisors to meet this demand and, importantly, they need to have the derring-do to test clients’ willingness to pay. Discounting and pricing concessions in this environment are a race to the bottom. Firm business economics are weakened, and families remain unserved.

Success factors

MFO success depends on four interdependent factors: capital, leadership, strategy, and disciplined execution.

Finally, both MFO strategy and execution are far too variable. Too few firms have adopted best practices from their industry peers. The best-in-class firms will be deeply networked, have competitive field intelligence and will be innovators ready to modify their strategy and execution in anticipation of client demand.

This article was adapted from James H McLaughlin, “Proscriptions and Prescriptions,” Investments & Wealth Monitor, January/February 2016.

Appendix

Core vs Adjacent

The economic future for all MFOs will be to stick to their knitting as they lead in the provision of myriad core or adjacent services. Families don’t believe that any firm can do everything well and firms are fooling themselves if they think that they can provide everything.

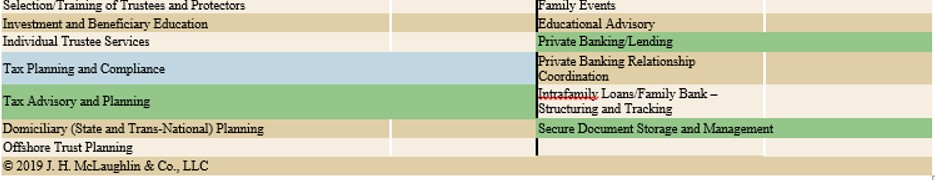

I use a “Master List of Services” as an analytical tool for multi-family and single-family offices to explore the efficacy of their service platforms. Should an MFO or family office faithfully complete this as an exercise, it presents a host of implications for maintaining client primacy and for their economics.

Core services are internally delivered services - services no one else can do better, that secure client primacy and that can be delivered profitably.