UHNW Institute

The Skinny on UHNW Wealth Management Models - UHNW Institute

Many UHNW individuals are and can be confused about the array of business models pitching for their business. This article - the first of a five-part series - explores the terrain.

As part a continuing series of analyses of ultra-high net worth client issues in North America and beyond, here is the first of a five-part overview by Jamie McLaughlin. He is chief executive of J H McLaughlin & Co, a member of FWR's editorial advisory board, and also a founder of the UHNW Institute, the not-for-profit organization. (FWR is the exclusive editorial partner of the Institute.) To view other UHNW Institute content, click on the button marked “UHNW Institute” under the “categories” section on this news service’s homepage. Readers can also find the Institute's website here.

Ultra-high net worth clients, including the most discerning families, are confused and challenged to understand the different wealth management models, their operating dimensions, service platforms, and capabilities.

The firms that serve them do not make it easy. One of the reasons potential clients hear the same thing from different firms is that the firms genuinely believe they are doing or delivering the same thing (or won’t admit that they don’t).

This muddle about who does what in wealth management is made worse by the fact that the term itself is undefined almost universally. Imagine, if you will, an industry that has not developed a generally accepted definition of its primary product. Welcome to wealth management.

How did we arrive at this juncture? A look at history offers some explanation. The industry that is wealth management today represents a loose amalgam of four different business models operating under four distinct regulatory regimes - all competing in the same space. They are:

-- Commercial banks;

-- Broker dealers;

-- Registered investment advisors; and

-- Trust companies.

Our intent here is to offer a five-part series (this being the first and introductory installment) that will unpack each of the four business models across several dimensions, including:

-- What are their ownership and capital structures?

-- What are their cultural norms?

-- What are their investment and non-investment processes,

service platforms and resources?

-- How do they price their services?

-- What are the drivers of their business economics?

-- What are their conflicts of interest?

-- How do they comply with the “fiduciary standard”?

-- As putative “trusted advisors (1),” how do they manage their

client relationships?

The accompanying article, A History of Wealth Management, is offered as a survey overview of the industry’s history and represents an essential element of our series. Our overall goal is to help investors better understand the various models and service platforms, and thereby to be able to better assess what they read and hear.

Defining the term

To start, we need to help clear the muddle by nailing down an

important definition. We define wealth management as

comprehensive, integrated financial planning and administrative

services for people with a lot of money. Wealth management is not

the same thing as money management. Money managers manage assets,

whereas wealth managers manage their client families’ financial

lives.

How much money is a lot? That could mean many different levels of wealth, but for a definition of ultra-high net worth we’ll proffer two tests or thresholds: enough so that meaningful assets will remain at the death of a surviving spouse, and thus wealth transfer planning in respect of the estate and gift tax regime is appropriate. In practice, when assets exceed the estate tax exemption. (2)

Enough so that there are excess or surplus funds available for investment management purposes beyond cash or household management requirements and asset-liability funding (i.e. education, retirement, longevity risk, etc.). Those assets could be “risk assets” invested for total return and/or require philanthropic planning for their tax-optimized disposition.

Given the above tests, a working number might be $25 million or $30 million. (3)

Only a decade ago, it was common for some firms to offer investments and nothing else yet call themselves wealth managers. This was often misleading and certainly confusing to client families. Today, in a welcome turn, comprehensive planning is showing signs of reasserting its rightful place as the foundation of wealth management.

As wealth management evolved over the past three decades, firms’ service models have come to incorporate a host of integrated disciplines and techniques of comprehensive planning to serve the needs and expectations of wealthy clients. It now includes non-investment advisory services that address wealth transfer, asset protection, tax planning, risk management, and philanthropy among an array of other services to serve the administration of their households. More recently, for the super-wealthy, the dialogue now includes issues related to family systems, family sustainability, and the very purpose of the money.

Finally, with the rise of information technology and an emerging

FinTech industry, client expectations have also come to include

data transfer and data assimilation for household financial

management and consolidated reporting with the emergence of a

host of digital, tech-enabled solutions. The importance of

quality assured, secure data cannot be overstated.

.

The economic framework

Contemporary wealth management can be seen as part of a broader

asset management industry or complex. In fact, the industry

exhibits many of the same common economic aspects as other

industries whose supply chain economics include a continuum of

manufacturers, distributors (i.e. sales) and consumers.

Applied to wealth management, the asset management complex includes asset management companies who produce various investment products, their distribution agents and the clients who buy or consume these products. An additional role of advisor emerges sometimes as a distributor or salesman and sometimes in a role as agent for a consumer. The advisor advocates for the best terms and conditions for their clients, often with the intent of disintermediating the manufacturer and/or the distributor.

When we examine the four primary wealth management business models, firms can play various economic roles - manufacturer, distributor or advisor - each having its own set of standards and incentives.

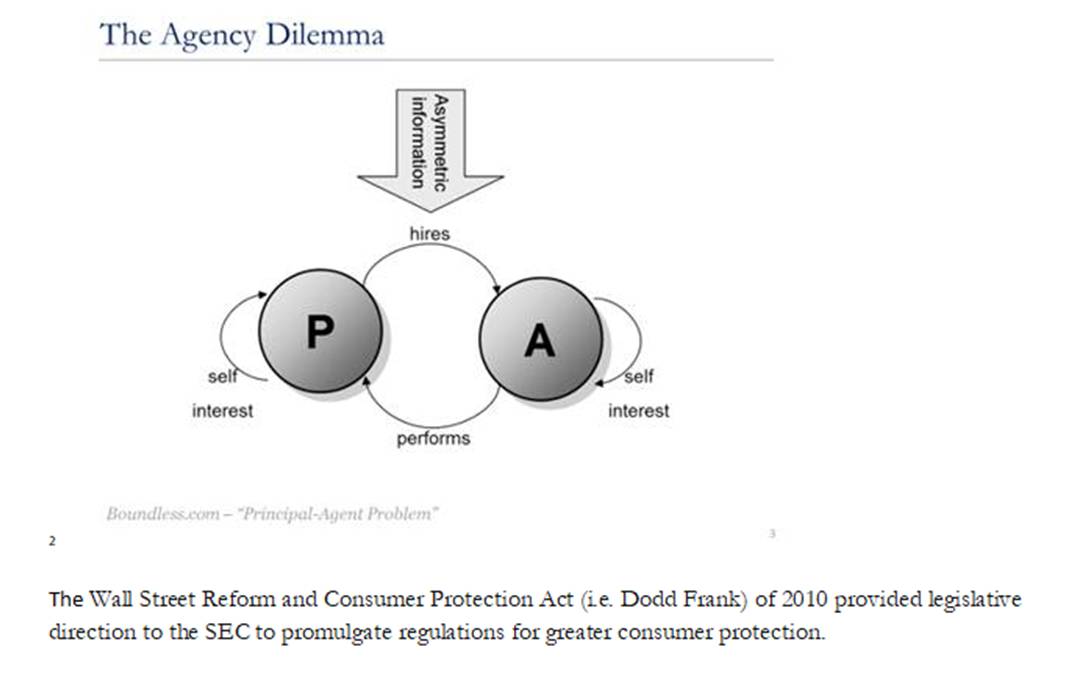

The agency dilemma

All financial advice has some inherent conflict of interest. Any

form of compensation for the advice creates some level of

self-interest and is unavoidable. However, clients can be better

informed of their advisor’s objectivity, how their firms’

incentives effect their behavior and objectivity, and the

potential for conflicts of interest when they render advice.

Understanding agency theory can illuminate some distinctions

between the various business models.

Agency theory is a management and economic theory that assumes both a principal and an agent are inherently motivated by self-interest. The predominant academic focus has been on the economic incentives and accountability frameworks between parties where the duty of an agent is to avoid conflicts of interests or the temptation of a potential conflict of interest when representing another party's interests.

When we apply agency theory to financial advice or wealth management, one reaches a simple interpretation - any financial adviser has a duty to disclaim and disclose all conflicts of interest to a client notwithstanding the interest of their firm or their affiliation to a parent company acting as a principal. This “agency dilemma” is at the heart of a pronounced shift in wealth management demand as the so-called fiduciary standard debate pits various corporate (i.e. principal) interests against a broadly applied fiduciary standard in the conduct of an advisor-client relationship.

Keep in mind, broker dealers who operate under selling agreements

with asset management companies are distribution agents for

another third party. Their agency duty is to a manufacturer

(internal or external asset management firm). Selling

agreements between manufacturers and distributors are not on

their face wrong, but they are wrong when they’re non-transparent

and/or where firm representatives intentionally mislead clients

that they are acting as a client’s agent by calling themselves an

“advisor” or other like-kind term that implies impartiality when

in fact they are salesmen acting as distribution agents for a

manufacturer of a product.

Despite recent efforts by the Department of Labor (DOL) in its

jurisdiction over retirement plans and the Securities and

Exchange Commission (SEC) pursuant to “Dodd-Frank,” the fiduciary

standard issue has not been settled and can be expected to be

debated for the foreseeable future. Certainly, “harmonizing” the

application of a fiduciary standard across various business

models appears unlikely.

Regardless of the regulatory outcome, the debate between various financial institutions has raised the issue as a matter of public discourse for investors. Clients are beginning to ask questions about their advisors’ alignment of interest with their own interests and about their advisors’ compensation systems and the incentives that those systems create.

The current focus on conflicts of interests and their disclosure can only be expected to increase. It will be arguably the fulcrum of client demand in the near future as clients become better informed and transparency in the information age becomes a sine qua non. While it is very hard to legislate ethics, with more information consumers have the power to force change.

In this context of the agency dilemma, who are clients to trust? "Trusted” means different things to different clients. Some clients view “trusted” with an emphasis on conflicts. Other clients view “trusted” as meaning an advisor who is candid and transparent and in practice puts the client’s interest before his/her own. There are some teams even at the most product-centric firms who do this and their clients are quite happy with them, despite the fact that there are real potential conflicts. Clients with these advisors value the advice they receive and are comfortable with the potential conflicts, either because they trust their advisors and/or they feel like they know about and can assess the advice they receive despite the conflicts.

Summary

While we have endeavored to define wealth management and apply

the definition to the ultra-high net worth client segment, the

term remains confusing for even the most discerning families.

Families tend to work with wealth management advisors for a host of reasons best summarized as relationship good will and not because they’ve examined each of the business models. They are too often ill-equipped to compare and contrast the various firm approaches and service capabilities.

With the above as context, in the next four parts, we will describe each of the four business models independently and offer observations on their respective advantages and limitations so that families can better understand the various business models and service platforms and thereby better put into context and assess what they read and hear.

Footnotes

1, While pursuant to the Investment Adviser’s Act both firms and individuals can be advisers, we use the term advisor.

2, For 2018, the exemption limit rose to $11.18 million per individual and $22.36 million per married couple. For 2019, an inflation adjustment lifts it to $11.4 million per individual and $22.8 million per couple. The increase in the exemption is set to lapse after 2025 reverting to its 2017 level of $5.49 million (plus an inflation adjustment).

3, Wealth-X and Deloitte define UHNW as $30 million. BCG uses a household definition of $100mm liquid net worth.