Banking Crisis

Inverting Bond Yield Curve Doesn’t Imply Recession – Morgan Stanley

The US bank and wealth management firm examines whether a change in the shape of US government bond yield curves is a red flag for recession, or whether it's a matter that should not unduly worry investors.

An inverted shape of the US government bond yield curve, caused by how yields on short-dated Treasuries are above those with longer maturities, doesn’t necessarily imply a recession is on the cards, because forces in play are unique, Morgan Stanley says in a note.

The huge economic disruptions and costs caused by COVID-19 lockdowns, spiking energy costs and rising inflation have been accompanied by rate hikes from the US Federal Reserve, moving the Fed funds rate from zero to a corridor of 0.25 per cent to 0.5 per cent. More rate rises are expected. Inflation has spooked markets. In February, the consumer price index rose 7.9 per cent from a year ago, the highest rate in four decades.

Banks and wealth managers are trying to work out how to position clients' portfolios at a time when rising inflation and the prospect of rising rates is forcing them to re-think asset allocations. The past decade has seen a flood of money into relatively illiquid segments such as private equity and credit amid a drop in yields on conventional government debt and listed equities.

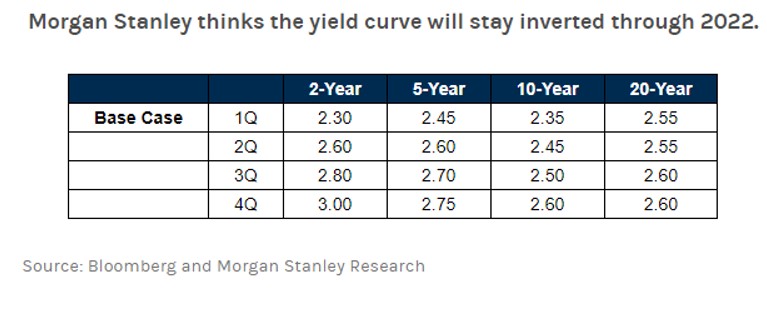

Recently, yields for two-year Treasuries moved higher than those of 10-year Treasuries, or what economists call a “2s10s” curve inversion. Morgan Stanley strategists think that the 2s10s curve will invert further and sustain that inversion throughout the remainder of the year. (See chart.)

“Historically, this has signaled an imminent recession. This time

around, however, the inversion has more do with near-zero

interest rates and strong demand for long-term Treasuries than

the health of the economy,” the firm said in a note.

“Overall, the yield curve has become less of a recession

indicator over the last two economic cycles,” Morgan Stanley’s US

chief economist Ellen Zentner, said. “And when we look at factors

in the economy that are typically signals of a recession, such as

job growth, retail sales, real disposable income and industrial

production, we don’t see an approaching recession.”

All things being equal, bonds with longer maturities typically need to pay higher interest rates to compensate investors for the additional risks that come with owning these fixed-income assets over time, the bank said. When a yield curve is “normal,” it slopes upward; the longer a bond’s maturity, the higher its yield. In the past, an inversion has flagged that investors collectively see more risk in the immediate future than down the road.

But the bank said that the past two economic cycles haven’t been typical. “In reality, yield curves flatten for a multitude of reasons, most of which aren't a reflection of investor views about slowing growth,” Matthew Hornbach, global head of macro strategy for Morgan Stanley, said.

The bank said that rate rises usually nudge interest rates for other bonds higher, but the effect isn’t always linear; at present short-term bond yields are increasing while yields for longer-term bonds have barely budged. This is because there is strong global demand for US Treasuries, as well as the US government’s own bond buying.

“Higher rates don’t always mean recession. The Fed is raising interest rates to combat inflation and keep the economy from overheating. While markets often have a knee-jerk reaction to higher interest rates, many times the Fed has raised rates without triggering a recession,” the firm said.

Morgan Stanley also argued that banks won’t stop lending, contrary to what some market watchers may fear. The bank said its research shows that bank loans grew during the prior 11 periods of yield curve inversion since 1969. And this year, they project loans will grow 7 per cent year-over-year.

“In the absence of growth headwinds from geopolitical events, curve inversion alone would not be a cause of concern for corporate credit, given healthy balance sheet fundamentals,” Hornbach said.