Tax

Florida Bound: Moving To A Warmer (Tax) Climate

There has been a trend of wealth firms moving to Florida, expanding operations there and, in some cases, even transferring headquarters to the state. This article probes the tax angles that have been a motivator, and offers words of caution.

A number of wealth management firms have bulked up operations in Florida, expanded businesses in the state or, in the case of Dynasty Financial Partners, for example, moved corporate headquarters to St Petersburg, from New York City. (We reported on its reasoning about that move recently.) There’s a growth story in the Sunshine state, and one of its attractions is relatively low taxes compared with more established financial centers. The cost of living is lower, more than compensating, so practitioners say, for lower incomes in some cases. (Another major wealth firm based in the state is Raymond James.)

Miami, Fort Lauderdale and other cities are growing; the state is also, for historical and geographical reasons, an important one for handling wealth from Latin and Central America. (See stories here and here.) Among other firms expanding in Florida are Goldman Sachs, which recently named its region head for Florida and Latin America, and has added hires in its private wealth management business; Rockefeller Capital Management has opened an office in Florida; Evercore Wealth Management opened a new office in Palm Beach; Landsberg Bennett Private Wealth Management launched earlier this year in Punta Gorda, Florida; and Boston Private appointed advisors as part of its work with a Florida-based firm. It is not all sunshine and good times, however: we have to recall that multi-billion fraudster Bernie Madoff preyed on wealthy people in Palm Beach, among other places; and the state does get hit by hurricanes.

In this article, Helena Jonassen, who is a partner and wealth and fiduciary advisor at Evercore Wealth Management and Evercore Trust Company, considers the tax angles of moving from one state to another, and talks about Florida’s position – and that of other states. Moves to new states are not as simple as it might seem at first glance, a fact that Jonassen draws out.

A number of recent changes, such as US tax measures in 2017 limiting deductibility for state and local taxes, have put a squeeze on states such as New York and California, and with important political implications. The issue also reminds us of how certain states, such as New Hampshire, Delaware, South Dakota and Nevada, are important tax jurisdictions in their own right.

The editors of this news service are pleased to share these views; the usual disclaimers apply of course, so do not hesitate to respond with a comment if you wish to do so. Email tom.burroughes@wealthbriefing.com or jackie.bennion@clearviewpublishing.com

When the Beatles released Taxman in 1966, the band members were subject to tax surcharges as high as 98 per cent. Within a few years, the Rolling Stones, the Kinks (who wrote Sunny Afternoon, another song about the surprisingly rock 'n roll subject of tax), David Bowie, Cat Stevens, and many others had fled Britain. Americans have never had that option. Unlike those of all other developed countries, citizens and permanent residents of the United States are taxed on worldwide income.

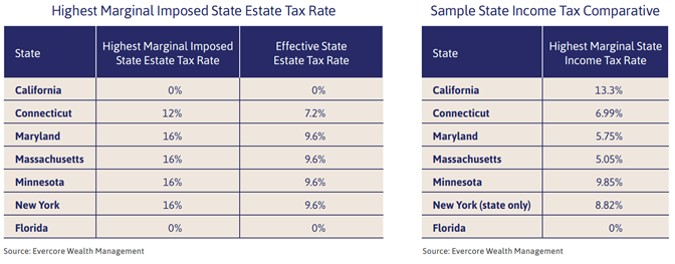

Tax exile in the United States tends to be a domestic affair, as families move from high-tax to low-tax or no-tax states. The differences can be startling – 8.82 per cent personal income tax and up to 16 per cent in estate tax in New York; none in Florida – as illustrated in the sample charts below. Just how important a role personal tax plays in these moves is difficult to measure. The real drivers can, of course, include corporate tax advantages, the climate, and recreational interests.

In any case, the tax angle can be a headache. State taxing authorities are increasingly aggressive in challenging moves. Each state has its own rules on whether a taxpayer is subject to their income tax, but most include a count of how many days the self-declared former resident spends in his or her former domicile, with six months being the general line in the sand. In New York, which is losing tens of thousands of people to Florida each year, more than to any other state, according to the US Census Bureau, a person is still considered a resident for income tax purposes if he or she spends 183 days or more in the state.

While the terms residence and domicile are often used interchangeably, they have very specific meanings for both income tax and estate tax purposes, as defined by individual state laws. Residence simply requires physical presence in a state, while domicile requires physical presence in the state and the intent to make that state the fixed or permanent residence. While a person can have a residence in many places, as a general rule, they can only have one domicile.

The more substantial the retained property, the more intense the scrutiny is likely to be. Where are the people and objects that are considered near and dear to the taxpayer? Business and family relationships, children’s school attendance, credit card receipts, travel documents, E-Z pass transactions, phone records, vet bills and more; name it and state authorities have probably thought to examine it to verify the taxpayer’s assertions.

The burden of proof falls on the taxpayer, not on the state. The individual must be able to show that not only has he or she spent the required time out of the state at another residence but also that the intention is clearly to change the domicile. While there is no bright line test that determines domicile, individuals can draw on all of the same materials in their defense, in the event of a residency audit. Location apps, which use cellular network, Wi-Fi, and GPS technology to determine location, can augment hard evidence.

It should be noted that there is no double jeopardy when it comes taxation. More than one state could claim that a taxpayer is resident for income tax purposes and likewise could claim that a decedent was domiciled in the state for estate tax purposes. While these instances are rare, residency audits are not – and they are nothing to sing about. Taxpayers who wish to change domicile – for whatever reason or combination of reasons – should follow a clear protocol, be mindful of the potential traps, keep meticulous records, and seek expert advice.