Tax

Anxious Times For IFCs After G7 Corporate Tax Accord

After the Group of Seven nations agreed on a minimum 15 per cent corporate tax rate, IFCs have started to address what they may have to confront. Offshore centers are in a position analogous to a competitive business confronting a "cartel." Several centers impose no corporate tax rates at all.

International financial centers - some of which have very low/zero corporate tax rates - have reacted to the G7 agreement at the weekend to set a minimum corporation tax base of 15 per cent. The move is designed to stop jurisdictional arbitrage on tax, but which also begs questions about sovereignty over tax policy.

As reported earlier this week, the Group of Seven major industrialized nations (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK and the US), agreed that businesses should pay a minimum tax rate in each of the countries in which they operate. Time will tell whether such a move will be joined by a wider group of nations, and whether national parliaments will, in fact, endorse it.

International financial centers such as the Cayman Islands, Jersey and the Bahamas have commented on the development.

The government of the Bahamas issued a carefully-worded statement which, like Jersey Finance, drew back from any direct criticism of the G7’s move, but its reference to the issue of “sovereignty” suggested some pushback.

“Notwithstanding agreement by the G7, the framework proposed by the Steering Group will require the consensus of the 139 countries of the Inclusive Framework on BEPS before going on to the G20 finance ministers for ratification later this year,” it said.

“The Ministry of Finance is conducting an assessment of the impact of these proposals and what implications they may have for the domestic tax regime of the Bahamas. The Bahamas reasserts its sovereign right to determine the tax structure best suited for the ongoing development of the country," it said.

Cayman Islands

In the Cayman Islands, the organization that represents its

financial sector, Cayman Finance, asserted that its “tax neutral”

status remained a key selling point. The Cayman Islands is a

British Overseas Territory.

“The Cayman Islands is a tax-neutral jurisdiction and our financial services industry is the world’s leader in international investment funds, which are internationally recognized as tax neutral. Cayman achieves tax neutrality in the simplest and most cost-effective way possible: it does not add another layer of tax on top of what is imposed by other jurisdictions. This enables our financial services industry to do what it does best, facilitating investment throughout the world, thereby driving global economic growth and prosperity.

"Our industry will continue to play this important role, much needed during this time of recovery from a global pandemic, following any implementation of a global minimum tax rate for multinational enterprises. Our tax-neutral regime recognizes the importance of taxing the right people, at the right place, at the right time. Indeed, Cayman’s tax information-sharing commitments enable more effective tax collection by other jurisdictions," it continued.

"Taken as a whole, Cayman’s tax neutrality and international commitments protect against tax evasion, aggressive tax avoidance, unfair tax competition and any tax harm to other jurisdictions. That’s a record we are proud of and will continue to advocate for in international standard-setting efforts.”

Jersey

Over in Europe, Jersey, a Crown Dependency that has UK links but

its own legal and political system, also weighed in.

“The reality is that these proposals have been ongoing for months - years in fact - in an attempt to try and tackle large multinational profit shifting, and ensure that, in particular, the big global tech companies pay tax in the places where they do business,” Joe Moynihan, CEO at Jersey Finance, said in a note.

“It was always the expectation that the OECD would take the lead and make representations in summer this year,” Moynihan said. “With the G7 having now agreed a number of measures and a way forward, the next step will be for the measures to be agreed by the G20 to gain widespread international approval. Again, that will be no mean feat, but we can anticipate progress on that later this year.”

He said aspects of the proposals are “encouraging.”

“The proposals are aimed squarely at tackling large multinational companies, particularly large tech companies, which are not a significant feature of Jersey’s business model,” he continued.

“Of course, multilateral changes to the global corporate tax environment will not be without their challenges. These proposed changes have the potential to impact all countries, and it is absolutely our belief as a jurisdiction that any reforms must be implemented on a level playing field, balancing the interests of small jurisdictions as well as larger ones; developed as well as developing countries,” he said.

The global tax environment is hugely challenging and this is a once-in-a-generation opportunity to provide some robust, sensible solutions to improve the international tax landscape and provide consensus and certainty - but it must be done right, consistently and with full agreement at international level,” he said.

Jersey's government appears to be unhappy about the minimum tax rate pact.

Jersey's chief minister John Le Fondré recently told President Biden that the latter should ‘look closer to home’ and pointed to low-tax regimes in states such as Nevada, Wyoming and Mr Biden’s home state of Delaware.

The EU parliament passed a resolution earlier in 2020 calling for jurisdictions with zero-rate corporation tax to be blacklisted..

Jersey has a "zero-ten" corporate tax code. The zero-ten system was introduced in Jersey in 2009 after the European Union Code of Conduct Group said that the island’s previous exempt-company-status regime was unfair. (Under that system foreign-registered companies were not taxed as long as they paid an annual fee.)

Today, resident companies in Jersey are generally taxed on worldwide income. A permanent establishment, such as a branch of a company, is taxed on profits attributable to the permament establishment. Non-resident companies are taxable on Jersey real estate income. Companies are liable to income tax at a rate of zero, 10 per cent, or 20 per cent on taxable income. The general rate applicable is zero, while the 10 per cent and 20 per cent rates apply to certain companies/income streams.

In the Isle of Man - another Crown Dependency - the general corporate tax rate is zero.

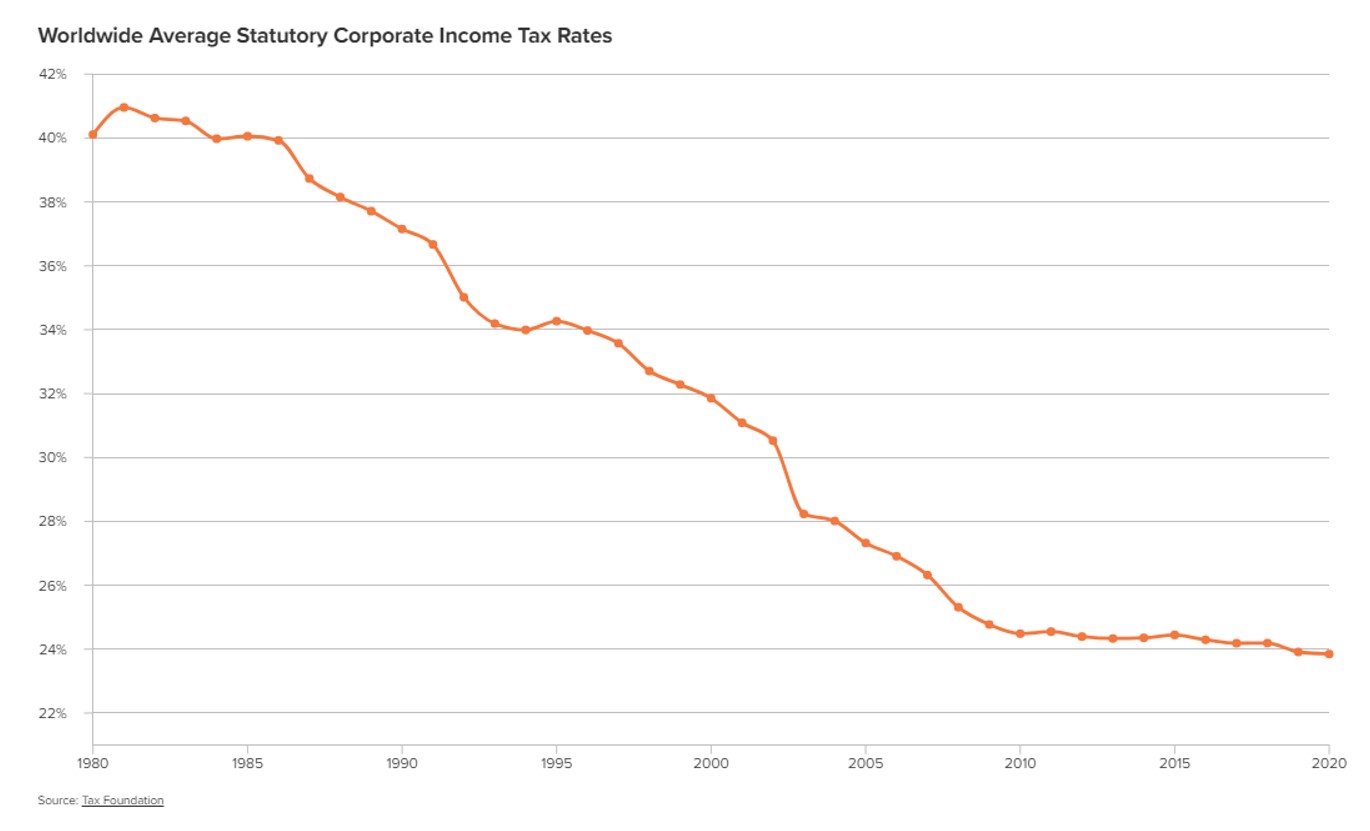

Corporate tax rates have fallen steadily over recent decades, as countries have competed to attract inward investment. This is sometimes branded as a "race to the bottom", even prompting calls to scrap corporate taxes completely and tax individual beneficial owners of companies instead.

Source: Tax Foundation.

(Editor's note: Sometimes the idea of countries setting minimum tax rate agreements is dubbed as a tax "cartel" because the argument is made that decisions about rates should ultimately rest with legislators in specific nations, that such "cartels" are self-serving and induce complacency, and because offshore centers create a safety valve when major countries go down a high-tax, high-spend path (as appears to be the case now). These may be sound arguments, but they are particularly difficult to make when emotions run high about corporations, such as the "Big Techs," finangling the patchwork of global tax regimes, and when the pandemic has ravaged public coffers. In the medium term, as we know from accords among oil producers (OPEC), such "cartels" can be hard to maintain because a producer/country will have an incentive to defect. Much depends on how low corporate taxes are. If they were to rise back into the high 20s, or 30s or more, then offshore centers would be under big competitive pressure to defy received wisdom. In the meantime, these are nervous times for the offshore world. A final irony is that one of the arguments for Brexit was for the UK to be able to restore sovereignty over its tax policy.)