Tax

A Global Minimum Corporate Tax - Smart Policy Or "Tax Cartel"?

Setting a global minimum corporate tax rate among major industrialized nations has the certain appeal of being simple. But it raises many questions about whether offshore centers will enable firms to circumvent the process, as well as a minimum-rate regime eroding the freedom of nations to set their own rates.

ZEDRA, the international corporate services, funds and wealth services firm, has weighed in on the transatlantic debate over US President Joe Biden’s desire for a global minimum level for corporate taxation.

Biden, bolstered by a Democratic majority in the House and Senate, wants to set a floor beneath which countries’ corporate tax rates cannot fall. Under the previous Trump administration, the US rate was slashed from 35 per cent to 21 per cent. Prior to this, the US had one of the highest such rates in the world. This was partly to blame for many US multinationals parking some of their overseas earnings abroad rather than repatriating them.

Last week, the US agreed to accept a minimum rate of 15 per cent, down from its previous target of 21 per cent. France, Germany and Italy have since said that this level was a good basis for securing an international agreement by July. A deal could be agreed by the Group of Seven countries as soon as June.

Media reports, however, have said that the UK is not minded to play along.

“There’s no doubt the UK wants a more effective tax system – after all, it’s one of the few nations which has implemented a Digital Services Tax policy whilst the OECD battles wider reforms – but its party line is that Biden’s plan still has many shortcomings with its ability to better tax tech giants as it focuses on where profits are recognized and where their value is created,” Adam Dunnett, director at ZEDRA, said in a note.

“In recent weeks, Biden’s proposal for a minimum rate of corporation tax has garnered more and more international support. It’s been dubbed as the best opportunity for a generation to curb corporation tax abuse and so it’s no wonder we’re seeing strong commitment from the likes of Germany, France, Canada, Italy and Japan,” he wrote.

“The UK has expressed the need for more detail on the proposal, and sources closer to parliament have suggested that there are other motives involved behind the scenes. These touch on the UK’s responsibility for some of the British-owned tax havens it has around the world. The UK also wants to be able to undercut competitors in the future and the Conservative party has only just proposed a hike in corporation tax in 2023 to address the record amount of borrowing and needs [for] this extra tax revenue,” Dunnett continued.

Some nations within the EU, for example (Luxembourg, Ireland and Malta) set low, single-digit rates. Biden and like-minded politicians want to limit the scope for such “tax competition.” On the other hand, critics argue that tax rates should be a matter for individual countries and their voters. The UK, after all, voted to leave the European Union partly from a desire to put parliament back in charge of tax, instead of “harmonizing” rates across national borders (often upwards).

Corporate taxes, as they ultimately fall on the shoulders of people in various ways (shareholders, employees, etc), have long been criticized because they encourage finagling of different jurisdictions' tax codes.

Commentators have also argued that tax competition has eroded rates, limiting the ability of governments to raise taxes for their spending plans. On the flipside, defenders of this sort of competition, such as Daniel Mitchell, senior fellow at the US think tank, the CATO Institute, argue that this encourages governments to limit taxes beyond what would otherwise be the case. Mitchell has suggested that such efforts to curb different tax rates are tantamount to creating a tax “cartel”.

“Countries with good tax systems will not have any interest in joining Biden’s global tax cartel. Instead, they will maintain their better tax systems and benefit from an increase in jobs and investment as the United States becomes less competitive,” Mitchell wrote in an editorial article on 20 May (Los Angeles Daily News).

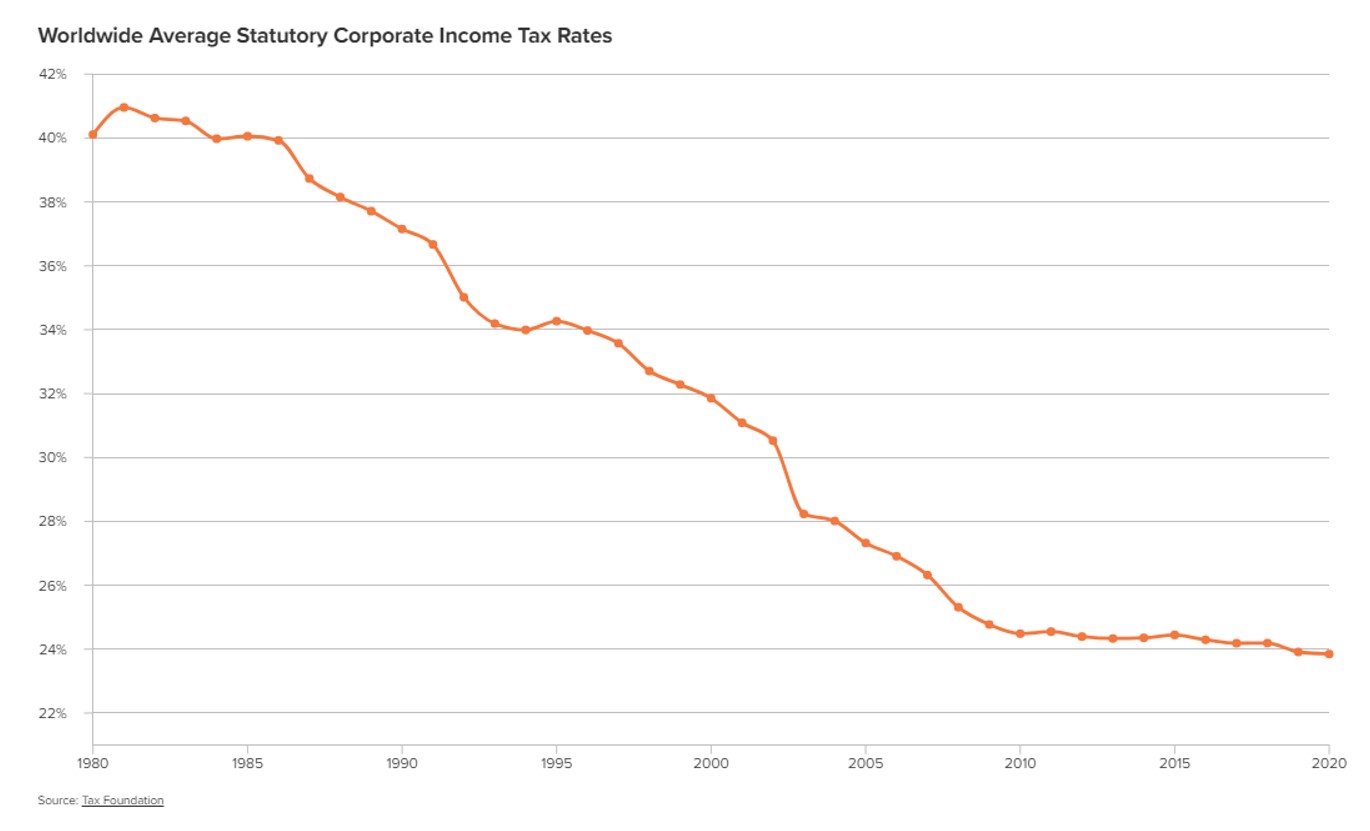

Corporate tax rates have fallen by about half since the early 1980s, as this chart, drawn from the Atlantic Council publication April 7, 2021), shows. (The chart references figures from the Tax Foundation.)